Anarchism seems to have attracted a steady growing interest since the late nineties. The number and quality of studies since, dedicated to the various facets of a movement previously and for a long time relegated to oblivion or derision, bear solid testimony to an apparently newly discovered relevance of the subject, translated both in its scholarly scrutiny and in the wider inspiration that anarchism provides for a variety of social and cultural expressions nowadays. The various works of Alain Pessin, Thierry Maricourt, Daniel Colson, Gaetano Manfredonia, Caroline Granier, David Weir, Richard D. Sonn, Peter Marshall, George Crowder, David Graeber, Vittorio Frigerio or Uri Eisenzweig for instance – if we were to mention just a few of the scholars that have dedicated to anarchism extensive and thoroughly documented inquiries, be it historical, literary, anthropological or philosophical – have already laid a ground not only for further researches on anarchism per se, but, most importantly, for researches stemming from an anarchist-inspired theoretical praxis.

Jesse Cohn is currently one of the most important and consistent voices in this yet fragile and minor field of inquiry. His first book, published in 2006, Anarchism and the Crisis of Representation: Hermeneutics, Aesthetics, Politics is a compelling analysis of anarchism in the wider cultural and theoretical context of “the crisis of representation”. Cohn proposes a rereading of anarchism as a rich, vivid and surprising, albeit almost forgotten, literary, philosophical and critical tradition, that could offer an alternative to the current exhaustion of the dominant critical systems. Anarchism, Cohn argues, is not merely a marginal political reflection, but a radical theory of meaning questioning language, representation and the speaking subject, and challenging at the same time the notions enforcing the reproduction of domination as a social and mental matrix. An analysis of the complex anarchist body of thought and practice regarding literature, language and meaning is thus relevant (or could be) not only from the point of view of a literary or cultural history (broadly speaking), illustrating the numerous anarchist infiltrations into modernist aesthetics, the various anarchist traces informing the so-called French Theory or the radical, sometimes insurgent expressions of the counterculture. In Cohn’s view, this is relevant, first and foremost to a possible further elaboration of an anarchist literary theory as a coherent and creative body of thought with wider implications: philosophical, political, social, aesthetic.

A common difficulty encountered by most of the researchers interested in anarchism and its multifaceted, fragmentary and discontinuous expressions, is that of the elusiveness of the subject matter. Can we actually speak of an anarchist culture, of anarchist writers or of an anarchist literature, if we are to accept that, nevertheless, a certain internal coherence is needed in order for such notions to withstand scrutiny? While some authors favor the associations and the multiple contact points between anarchism and the aesthetic avant-gardes, others, on the contrary, notice the quite significant vein of popular and proletarian culture associated with the anarchist milieus, vernacular or conservative in style and, not rarely, well dismissive of the modernist experiments.

One of the main questions animating Jesse Cohn’s Underground Passages. Anarchist resistance culture, 1848-2011 is precisely that of the invariants to be found in the diversity of cultural forms that the generations of anarchists have created and shared as forms of resistance.

The first part of Jesse Cohn’s book is an introduction in which the author states the core questions animating his inquiry, while also explaining some of the terminological choices he made, especially when dealing with terms semantically ambiguous, yet heavily circulated, such as “resistance culture”, “anarchism” or “anarchist literature”. The main intention of his research is “to examine the ways in which anarchist politics have historically found aesthetic expression in the form of a «culture of resistance»” (4). Borrowing Daniel Colson’s suggestion of a three-part historical model of anarchism, Cohn distinguished roughly three periods: the appearance of anarchism as a political philosophy, linked to the revolutionary movements of 1848; the second period or the period of practical elaborations of the anarchist idea, stretching from 1864 with the creation of the First International and ending in 1937 with the defeat of the Spanish and Catalan Revolutions; the third period marking the return of the anti-authoritarian ideas during the sixties: Situationism, poststructuralism, the Dutch Provos etc.

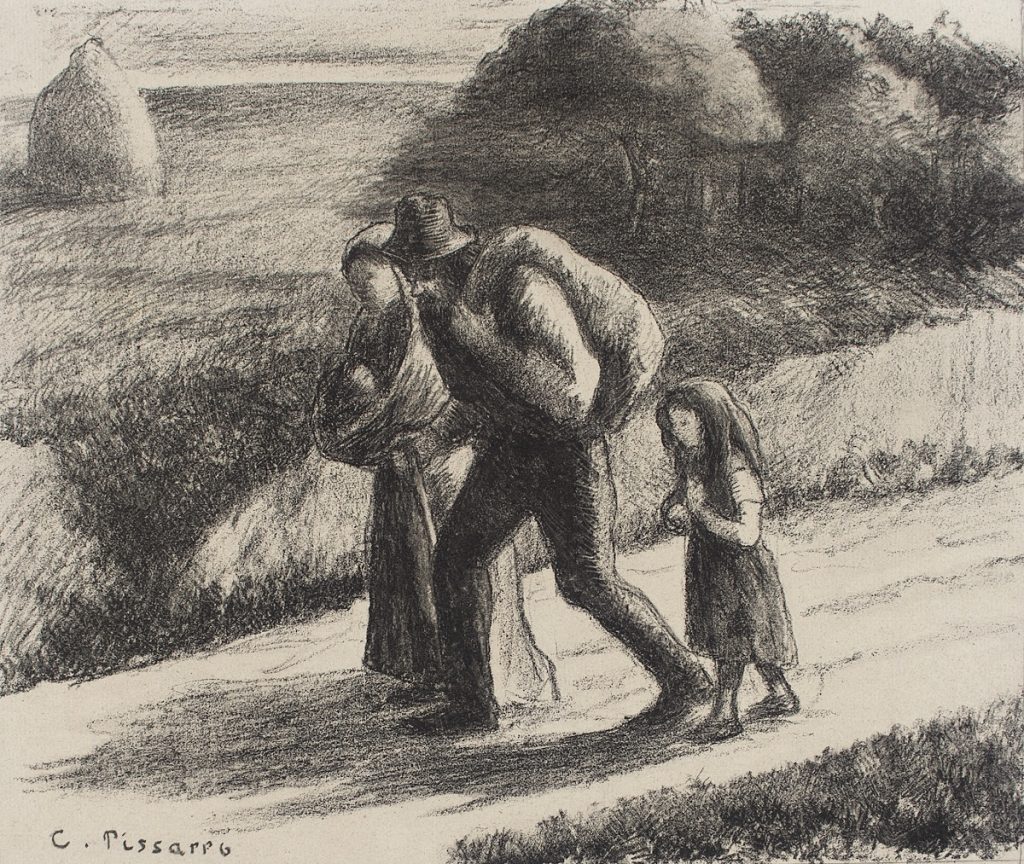

Anarchist resistance culture refers both to a specific way of life and to the production of cultural artifacts as instruments of struggle or means of coping with specific situations. When speaking of an anarchist culture, Jesse Cohn has in mind the cultural expressions and practices associated with the various anarchist milieus, rather than the anarchist-inspired modernist avant-gardes. The latter, Cohn says, were never firmly connected to the militant and anarchist communities. On the other hand, the anarchist conception of resistance is a radical one, contesting the totality of the social structures based on authority, domination and privilege, as well as the legitimacy of all the notions justifying them: State, Family, Nation, Church, Law, Progress. This in turn entails an experience of total resistance that is also assumed as an experience of (self) exile, of irreducible marginality and vagrancy. One of the most touching and revealing images of this particular and paradoxical existential positioning, both imposed and assumed, is the archetypal figure of the “total anarchist” as the tramp, the hobo, the vagabond poet and worker, le trimardeur (Alain Pessin). It is precisely this permanent exodus situation that the anarchist resistance culture is a response to, Cohn believes, as well as to the simple moral question of how to live through an apparently inescapable world of domination and oppression: “Anarchists practice culture as a means of mental and moral survival in a world from which they are fundamentally alienated” (15).

The second part of the introduction discusses the notion of anarchist literature. There is a primeval distinction to be made, Cohn insists, between “literary anarchism”, as comprising the works of modernist writers often sympathetic towards anarchism, and the actual literature linked to the global anarchist movement. Nevertheless, the “anarchist literary canon” seems to have included, alongside works from middle-class committed writers such as Octave Mirbeau or Bernard Lazare, a substantial number of works from non-committed authors, such as Zola, Tolstoy, Whitman, Oscar Wilde or Ibsen, as well as a quite significant literary production from working-class anarchist militants with no literary credentials. While anarchist literature was indeed primarily linked to the working-class movements, there is no synonymy between proletarian literature and anarchist literature. As Michel Ragon, cited by Jesse Cohn, noticed, the anarchist vision is somewhat different, more radical and broader in scope, “more philosophical than descriptive” (53). Anarchist literature seems thus to be marginal both to the classical canon of literature and to the “minor” proletarian literature. Its radical minoritizing functioning and practices have seemingly pushed it time and time again “en-dehors”, into uncertain, precarious and “refractory” positions, multiplied in as many elusive tunnels and points of departure.

The references to anarchist literature are, in general, as Jesse Cohn illustrates, dismissive. Some of the critics associate it to mere propagandistic expressions, having an overtly didactic intent and being all in all quite similar to party literature. There is seemingly “an incompatibility of literary form and anarchistic content” (30); or, as David Weir put it, social progress is not a guarantee for innovative forms of art and vice versa. The marginality of the anarchist literature and its minor status are however contrasting with the extremely rich, in form as well as in quantity, literary production. At a closer look, this apparently paradoxical situation can be understood nevertheless by referring to the anarchists’ comprehension of the practice, circulation and reading of literature. Addressing an “unstable, heterogeneous and marginal reader” (38), often consisting of deportees, immigrants, precarious working-class members, artisans, “declassés”, tramps or even sympathizing middle-class professionals, anarchist literature had to be accessible to all. It also had to respond sometimes to a precise pedagogical function, as many anarchists lacked a formal education. It is no wonder that, alongside the deeply engraved association between the anarchist and the bomb-throwing terrorist, the association of the anarchist with the “savage” autodidact, the bad, misguided and compulsive reader is not less frequent (as Vittorio Frigerio demonstrated in his excellent essay La littérature de l’anarchisme. Anarchistes de lettres et lettrés face à l’anarchisme). Other than that, there is a distinct communitarian function and communal participation associated with the anarchist literary practice, which in turn constitutes the anarchist discourse as an open-ended dialogue, challenging and reformulating the classical functions associated with literature, authorship, readership or critique.

The second part of the book, “Speaking to others: Anarchist poetry, song and public voice” tries to broadly illustrate the poetical tradition associated with the anarchist movement. In order to dispel any possible confusion, Jesse Cohn stresses from the start the fact that “the anarchist movement did not depend on the avant-garde for its poetry. Rather it developed its own poetics” (71). He also argues that the foundation of the anarchist poetry is the long standing tradition of the anarchist song, carried by the emblematic figure of the anarchist tramp. Poetry is thus understood as being a situated, performative act with a clear communal function. Very interesting and revealing is the analysis of the shift, after the Second World War, of the anarchist poetry from public modes of address to a more hermetical, introvert, withdrawn poetics, also affected by the corresponding Surrealists’ turn towards anarchism. It seemed as though language had been irreversibly contaminated, put “beyond poetic repair” (106), falsified, alienated and with it any real possibility of a community that would not be already corrupt by coercive institutions and by an anonymous social authority. It is in this context that Paul Goodman advanced the argument of poetry as the “physical reestablishment of community”, in a way redeeming the idea of “conspiracy”, of an intimate circle that seemed to be so dear to Bakunin. This “reverie” of enclosure was inspired nevertheless by the same anarchist idea of a performative poetry open to all, a collective means of creation and resistance, a way of enacting a “we”. It encouraged not only the old anarchist dream of creating a new language, but also the equally anarchic idea of a collective reappropriation of words. It is along these lines that anarchist poetics radically challenged the old notions of poet, of reader, of author or of text, simultaneously questioning the dichotomies of individual and community, of unity and multiplicity etc.

In the third part of the book, “«Out of the bind of the eternal present»: Anarchist narrative”, Jesse Cohn takes on a comprehensive and extensive presentation of the anarchist fiction and the types of anarchist narrative, also including a chapter about the anarchist theater. As in the previous parts, Cohn’s first concern is to refute some of the uncritical assumptions usually made about the anarchist fiction. Either assimilated to utopian writing or, on the contrary, to a form of socialist realism, the minor anarchist “art social” is by no means a monolithic, rudimentary body of works. While equally critical towards the modernist experiments, the realist or naturalist novel or the utopian disciplinary dreams, anarchists have developed their own practice and understanding of fiction, closer to what Ursula K. LeGuin called “a strange realism”. Literature, thought most of the anarchist critics, should not be a mere representation of things, a sterile depiction of the given, thus tacitly endorsing the status- quo and disciplining the reader into confounding reality with a particular configuration of it. It should, as Proudhon and Kropotkin wrote, include the inherently order of “the ideal”, of “the possible”, which is never separated from the real itself. As Jesse Cohn writes, “the staging ground for the anarchist narrative is precisely this heterotopian space caught between reality and utopia”, this “area of darkness that the novel should illuminate” (160).

An extensive presentation of the various anarchist narratives, from the “outcast narratives” or “anarchist road-stories” to the anarchist “ambiguous utopias” ensures a vivid illustration of both the different narrative and aesthetic strategies of the anarchist writers and, most importantly, of the “core ethic” and world-outlook that they are a testimony of. There are several narrative techniques employed by anarchist writers to “ward-off enclosure”: using shifting point of view, producing uncertainty by obscuring the auctorial voice, displacing the reader by the dystopian inversion of the present, etc. Resisting the disciplinary function of the mirror turns into a “prefigurative” art of possibilities signaling to the fact that “more is always lurking beyond the edge of the narrative frame” (Caroline Granier, cited by Cohn, 277).

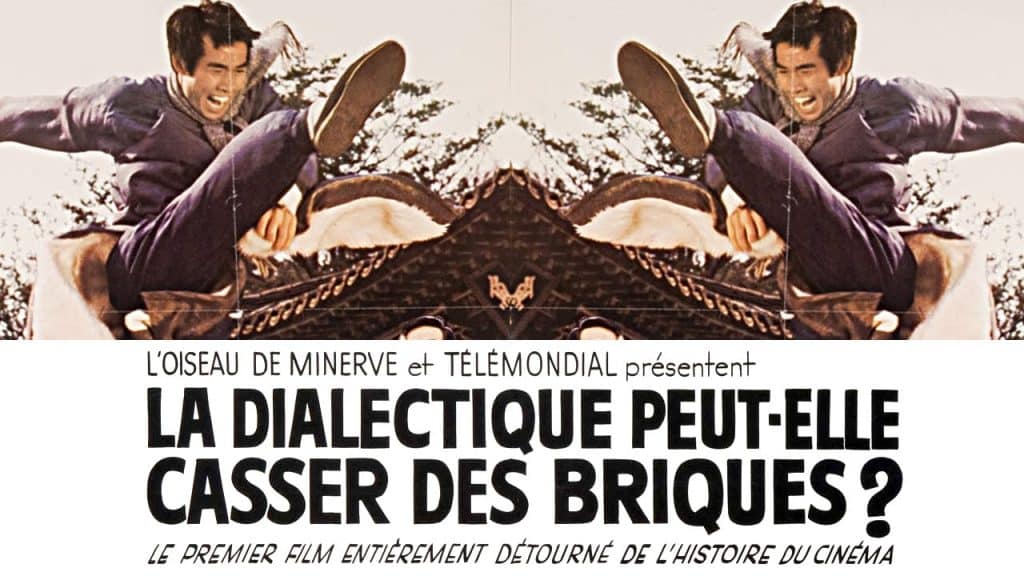

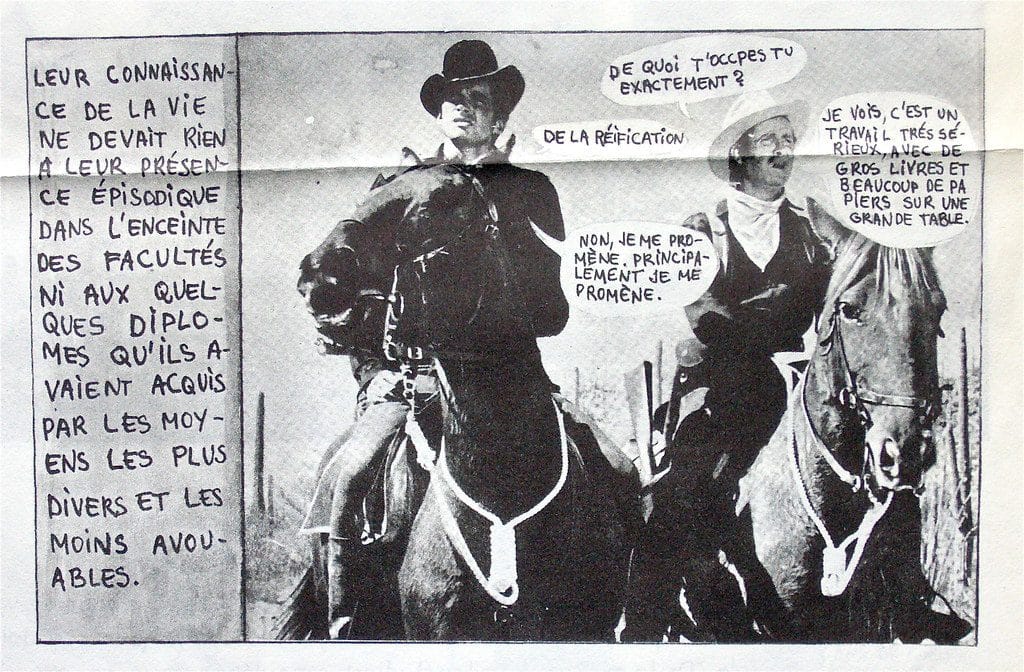

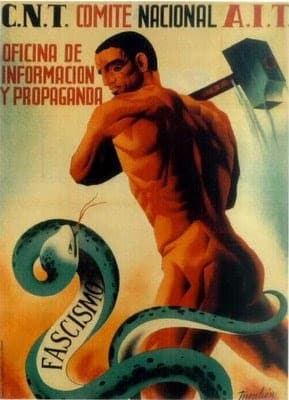

The fourth part of the book, “Breaking the frame: anarchist images”, is dedicated to the presentation and analysis of the anarchist visual culture, including a chapter dedicated to the almost unknown anarchist cinema. Jesse Cohn first takes us through the early anarchist representations of men and women in posters or illustrations. Furthermore, he discusses the aesthetics of the anarchist journals, including the titles, fonts and layouts, providing a significant array of reproductions and examples in support. Caricature and the comic strip are two of the most important anarchist visual practices. While the “wordless comic” is considered to be in a sense the “prototypical anarchist genre”, the method of “détournement”, consisting in “the creative appropriation of cultural commodities for subversive purposes” (313) seems to have had an equally lasting impact. The détournement can in fact be considered one of the preferred anarchist methods of cultural contestation and of cultural production, a form of parodical “poaching” of signs, symbols, texts, tunes or images. Like the para-songs, the appropriation of the “Lord’s tunes for the Devil’s work” (98), the visual détournements of the situationist cinema for instance function as resistance and critical tools, using the material provided by the all-encompassing “society of the spectacle” in order to decreate it, to dislodge it, “restoring a sense of possibility to the already filmed world” (Agamben cited by Cohn, 366). Much like the anarchist contestation of the realist mirror as a mere disciplinary and alienating discourse, the early anarchist conception of cinema seemed inclined to a similar judgment regarding the new form of popular entertainment. However, similar to literature, the anarchists did not take “the rejectionist route” (347) and tried instead to create a cinema of their own, aimed at offering an alternative, an antidote to the conventional, manufactured version of reality offered by Hollywood. French anarchists event put together a studio in 1913, “Cinéma du peuple”, while, during the Spanish Civil War and Revolution, an anarchist film industry seemed to have taken shape under the auspices of the anarchist CNT, producing a number of documentaries and a few fiction films. Resembling Bernard Lazare’s preoccupation for an “art social”, the anarchists tried to put together a “cinema social” (348), a form of educational cinema for all, with a distinct communal and pedagogical function. Yet, while the rich anarchist literary production could easily sustain the creation of a “counter-public” and of “counter-communities”, the anarchist film production was scarce and of low appeal to the public. Moreover, the crushing dominance of the visual language of Hollywood and Soviet cinema at the time seemed to leave no formulations available, no interstices, and no place for an anarchist consistent cinematic expression. The challenge of an “already filmed world” (366) is precisely the challenge to which the anarchist resistance culture responds. One of the best illustrations of this response is the work of filmmakers like Guy Debord or René Vienet, who use precisely a technique of “de-creative repetition” or “détournement” (369) as means of disruption, an example of which is Vienet’s film of 1973, La dialectique peut-elle casser des briques?, where a kung-fu movie is dubbed over with dialogues mimicking the rhetoric and the jargon of the “sectarian left”.

The different narrative, visual and aesthetic techniques used by anarchists, such as deformation, caricature, inversion, de-familiarization, narrative decentering or détournement, correspond to a form of strange, disobedient repetition of the apparently inescapable same, to that “area of darkness” (160) that is both a subtraction and an affirmation of the possible. Jesse Cohn concludes his study questioning the relevance that the anarchist resistance culture and its various expressions have for “the future of anarchism” (379). By discussing the afterwar period, when anarchism ceased to have a significant popular following and the anarchist culture took on a modernist, individualist, hermetical turn, Cohn argues for a resistance culture that would not be unreadable, thus running the danger of self-closure and isolation, in favor of a more porous anarchist counter-communities, opened “out onto a wider, more diverse public sphere” (378). In other words, anarchism needs to retrieve “the possibilities that have been lost or obscured by the passage of time” (390) and to evolve again as to regain its popular voice and its collective power of creation, becoming thus relevant for a larger public. The problem raised by Jesse Cohn is not a problem of status, but a question of connection, imagination, creation and contamination. It is also a question of countering the hegemonic and authoritarian discourses that discipline people into not looking beyond the “narrative frame” (here be dragons!). This is why he considers a poetics of “self-imposed exile” (384) a failed line of flight, a collapsed tunnel, a dead end.

Underground passages is a remarkable book for a number of reasons. First of all because it favors a comparatist approach that tries to encompass a rich array of anarchist expressions, both geographically and historically. It offers thus a precious glimpse of vast and almost unknown territories that researches on anarchism rarely venture into. Alongside examples from the better known Catalan, French or American anarchist writings and art we can find references to Japanese, Chinese, Cuban or Brazilian authors and critiques. This in turn underlines one of the (many) paradoxes and hazards that the researcher encounters when dealing with such a particular subject as anarchism. While it remains a minor and marginal movement, anarchism’s elusiveness is somewhat due to its particular plasticity and its farreaching cultural influences and multiple transformations. What usually ensues is an unexpectedly fragmented and vast field of research that upsets any predetermined sense of direction, inviting instead the actual creation of research situations and pathways and thus inevitably contaminating the research itself. This might be a reason why studies have so far preferred localized approaches, either by following the lines of contact with specific themes, such as David Weir’s compelling essay Anarchy & Culture. The Aesthetic Politics of Modernism, or by focusing on certain periods and specific literatures, such as Caroline Granier’s excellent Les briseurs de formules: Les écrivains anarchistes en France à la fin du XIXe siècle. Secondly, Cohn’s essay proposes an equally noteworthy and bold exploration of the anarchist culture by taking into consideration the way anarchism has adapted to the various media available. Hence, the analysis is not limited to poetry, narrative or literary criticism, but includes extensive references to the specific anarchist visual culture (illustrations, comics, caricatures) and a quite interesting incursion into the anarchist cinema. Taking up such a broad comparative task, stretching across genres, medias, languages, cultures and historical contexts, especially when dealing with such an elusive subject as anarchist culture, might prove to be hazardous, one might say. However, instead of just drawing up an inventory of the various anarchist cultural practices or artistic expressions, Jesse Cohn rather tries (and he is successful) to transmit the dynamic of cultural realization of anarchism as a form of resistance. If we were to paraphrase Murray Bookchin, the understanding of anarchism here at work is that of a “core ethic”, a certain way of doing and undoing things, articulated in different historical idioms and situations. Cohn’s book, while excellently documented and well constructed, is also a fine example of anarchist writing. The scholarly thoroughness, the precision of the style and the plasticity of the arguments can, in a sense, be misleading. The actual experience of reading can be quite different from that of a scholarly book. The impressive number of references, of examples, of issues debated, conveys a certain feeling of porousness, of a multiplicity escaping the actual frame of the exposition. On the other hand, the sometimes striking examples given to illustrate otherwise complex notions can act like triggers, what Alain Pessin called “incendiaries of the imaginary”, images generating and inviting a multitude of loose associations.

Altogether, Underground passages is a multifaceted rich text, opening numerous possible paths of inquiry and reflection, ranging from literary theory and aesthetics to philosophy and cultural analysis. In this sense, the essay is a valuable continuation of Cohn’s proposition of formulating a compelling anarchist alternative to the current critical practices and models. At the same time, by the variety of issues covered, as well as by the plasticity of the exposition, the text invites multiple readings and uses that are not exclusively confined to the academic or militant spectrum.

This review initially appeared in Metacritic Journal for Comparative Studies and Theory, 2.2, December 2016.