Vrijcoop is a Dutch rental housing network founded in 2015. Its aim is to provide solidarity housing to its co-projects and its members. The idea and the need for solidarity housing has its roots in the squatting movement which tried to transform abandoned, unused real estate into community and collective spaces, to re-introduce them into the cultural, community and/or housing circuit. On the other hand, it came about based on the realization that the constant expansion of the Dutch housing market leads to on-going dismantlement of safe and equitable housing conditions for renters. Solidarity housing according to the Vrijcoop’s model means that all its house-projects are free and able to own and manage their spaces. And this happens in a manner that their houses can never end up on the housing market again. Vrijcoop (based on the model of the German Mietshäuser Syndikat) prevents the selling and the re-commodification of these houses. Rent also gains a new meaning: while it stops contributing to the growth of the private wealth of a private owner, which – even when it comes to people’s homes – only follows its own private logic, it becomes an investment into a common good by directing it towards maintenance and the creation of new housing-projects.

This interview was made within the framework of the Solidarity Workshop and its part of a series of interviews with members of European housing cooperatives/networks. The aim of the series is to popularize European housing cooperatives. The Solidarity Workshop is a self-organized initiative, a nascent workshop with members from Cluj and parts of Szeklerland region and its long-term goal is the creation of a housing cooperative model in Romania. You can also read our first interview with the German Mietshäuser Syndikat here.

Zsolt Levente Dobrai: First of all, could you please introduce yourself, tell us about your involvement with VrijCoop? What kind of projects are you currently working on?

Jan Geurtsen: My name is Jan Geurtsen and I have been a resident of Amsterdam for a few decades. I have seen the housing situation become increasingly more difficult in those years. For the last fifteen years I have been involved in the process of securing spaces for collectives as a goal in itself, in the years before that, as an activist, I have been using collective housing, mostly squats, merely as a means to a broader housing struggle. Now I am convinced this question is more important than that. The slogan “housing first!” that is used in social work is also applicable to activism. Initiatives in building a stronger society start with securing housing for the movement and its work. So, yes, my conviction is that solutions do not come from above. The political system is forced to act by giving a working example, not by begging for a solution. I am very sympathetic to the struggles such as for Right to the city, but I think we should start one level lower, with collective solidarity and mutual help.

Could you please – briefly – fill us in on the history of the Amsterdam squatters movement? On your website we can read about 9 homes out of 20 which were successfully squatted in 2003. We can also read about the criminalisation of squatting: when did all of this happen and how can the squatting movement survive this criminalization?

Although I have participated in the squatters movement many more years than the average people last, I can only give my perspective on the squatters movement as a whole. In short: as a classic movement it had its roots in a broad share of society, and with that it was able to secure legal protection for squatters. In the early 90’s a tipping point came, when less people were dependent on the movement for housing and squatting was somewhat too easily experienced as a right and as part of the housing system. Also, a rising consumer mentality gave way to a growing number of so-called anti-squat companies [Antikraak], that provided a service to landlords by placing inhabitants in empty properties to prevent them from being squatted. The people living in such buildings would in previous times have lived in squats. Also, at first the landlords were paying the anti-squat companies for their services, and later this switched, now the inhabitants, the so-called anti-squatters, are paying a rent price to the companies and the landlords get a free service. In the end: less people actively support squatting and at some moment the real-estate lobby gained the support of more and more political parties, while the political discourse has made a shift to right-wing populism.

About the law on housing: in 1994 the law already changed a bit for the worse, and in 2003 the first discussion rose for a full criminalisation, while in 2010 (1st of October) the criminalization law came into effect. It has taken the real estate decades to shift the tables. Somewhere in the middle of this, in a neighbourhood in the east of Amsterdam in 2007 we founded Soweto. Because we felt something was missing, but mostly because something was possible. Besides squatting houses and making cases against landlords and showing what they are doing wrong, we thought we could organise ourselves and show how we think collective housing could be done instead. Without the slumlords, without the state and the semi-public/semi-private housing providers of the Dutch housing system.

Could you talk about the housing situation in the Netherlands? What is the housing market like? Who gets to buy, who doesn’t? How big is the public housing sector and why is it shrinking?

There is no public housing sector as such. It has all been privatised in the 90’s. There are no government-run housing providers. Instead, these privatised housing providers has been set up, initially strictly regulated and state subsidized. With the final privatisations though this also changed. From then until now these so-called housing associations [Woningstichting] are free to do what they want, as long as they do what the state wants.

There have been a few scandals around the time of the banking crisis of 2008 and the real estate lobby has used this as the moment to curb the position of the housing associations, in effect seeking to push towards more marketisation of housing. The housing associations have been shrinking some, but are still comparatively big. The focal point of this struggle of the market parties against the semi-public institutes is the so-called tenancy tax. Its target was obvious, an extra tax has been imposed on every house that is rented out below a certain rent limit [which is applicable for social cases – trans. note]. Even worse, the tax is based on the market value of the house and as such, providing cheaper housing in expensive areas is punishable with a tax.

With the Housing Act that came into effect in July 2015, the concept of the housing cooperative has been introduced. This provides an opportunity for sitting residents of social rental housing entities to jointly take over their homes. What does this taking over mean exactly from the perspective of the cooperative housing movement?

The 2015 law is an integral reorganisation of the housing structure. This law is a mixed blessing at best, since it contains for example the low rent tax as well as the concept of the housing cooperative. And the part on cooperatives does not grant any concrete rights. There is for example no collective right to buy. The housing associations with this law are now only allowed to sell to another collective entity, while before they were forbidden to do so. There are still more limitations than possibilities.

On a more positive note, the whole legal framework that is being built around these so-called housing cooperatives is being shaped by people with an activist mindset and this is directly in line with the Soweto structure’s goals: questions regarding who provides the land or the building, the attitude of the local authorities, how can crowdfunding be incorporated into the financial structure, up to the bank that is solely financing these projects in the Netherlands: the German GLS bank – are being discussed.

Could you tell us what exactly is Soweto, Bajesdorp and projects like Pieter Nieuwlandstraat 93-95? What are the main features of these projects and spaces?

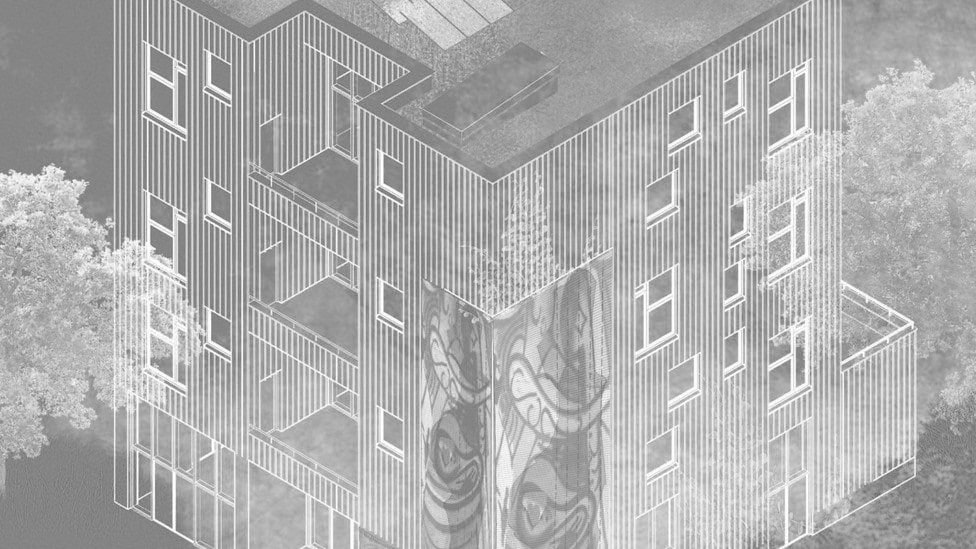

So yes, the story of Vrijcoop started with Soweto and Soweto started with the squatters movement. Soweto is the first attempt at a structure, Nieuwland is the first project realised within this structure. Vrijcoop is the second attempt at a structure and Ecodorp Boekel is the first project within this structure, while Bajesdorp is the second. In 2014 the first people moved into Nieuwland and the people who moved into Boekel, they moved in in the late fall of 2020. Bajesdorp will be finished in about two years, hopefully. What these projects are like or what they will be like in a few years is up to the groups in them themselves. What Soweto and Vrijcoop contribute to the individual housing projects is that later in their lifespan, they will not have to face the classic threat of the inhabitants selling the house for a profit as they get older, or the other way around that the structure around them decides to sell the house against the will of the inhabitants. This last risk is one of the reasons we went from Soweto towards Vrijcoop. Since Soweto is still the landlord of Nieuwland, but with Ecodorp Boekel or Bajesdorp Vrijcoop cannot act as a landlord.

How would you describe the role of the Vrijcoop model within a broader anticapitalist movement? Did you guys think of the possibility of collaborating with other anticapitalist structures with the aim of creating a solidarity economy ecosystem?

The full deconstruction of the concept of landlord, which is the main direction of Vrijcoop, is sometimes also called the neutralisation of capital. Meaning that the impulses normally associated with capitalism – like striving for personal profit against others etc. – must be exceeded. We think Vrijcoop has already done well on these terms. Then again, I think Vrijcoop is only one of many possible ways to achieve this, and related to a different national legal context it is as good a translation of the basic ideals as the German Syndikat or the Austrian Habitat.

Tell us about the relationship Vrijcoop has with groups and/or spaces like De Groene Gemeenschap, Meer Dan Wonen, Stad in de Maak and Rijkshemelvaartdienst.

Looking at the different allied projects of Vrijcoop, they vary wildly in backgrounds. De Groene Gemeenschap is a ten-year-old project, but owned by a housing association, and is threatened in its existence by the laws that govern the housing association, so they want to break free into the solidarity economy. Meer dan Wonen is a group on hold that is looking to buy a collective house in an area of the country notoriously populated by rich people, so looking for an option to buy something rather than paying high rent or owning individually. Stad in de Maak is a group that has been supporting a lot of anti-squat groups to find housing, but realising these stories always end are searching for ways to get these projects a permanent basis by buying the houses of housing associations and from local authorities. So far with no success. Rijkshemelvaartdienst is a project existing many decades and have built up as squatters an old industrial building, now many of them had raised families there and are looking towards securing the building for the future, knowing the national authority owning the property is likely to sell it at some point – otherwise the building would probably be demolished. Ecodorp Boekel is a group that over many years have searched around the south of the country to build sustainable housing. And have finally gotten everything together and gained national interest at the same time. For all of these projects Vrijcoop means an insurance for the future.

VrijCoop was established in 2015, what is its legal structure exactly and how does the financing work? How many people are actually renters, what is the structure of rental redistribution and the structure of loan repayment? And what is your current relationship with the Mietshäuser Syndikat?

In short: every project has two entities: one is made up complete of the inhabitants and organises all the daily matters of the project themselves. The second entity, we call it the real estate entity [vastgoedvereniging, VaVer] is made up by the inhabitant entity [bewoners, BeVer] and Vrijcoop [vereniging Vrijcoop] collectively.

In details: legally all three entities are associations [vereniging] under dutch law [vereniging ex art 2:26 BW e.v.]. Vrijcoop and the inhabitant’s entity both are members and have a veto in the real estate entity, when it comes to longer term decisions: this way neither Vrijcoop nor the inhabitants can decide to sell the house, syphon out the capital or change the structure. This makes the real estate entity a relatively safe investment, people can lend their money, knowing that this will not make the inhabitants rich in the future, so they are more likely to give loans. The inhabitant’s entity as a whole, pays rent to the real estate entity. The real estate entity invests in maintenance and pays back loans according to a collective plan. If at the end of the loans there is still money coming in the money flows to other future projects that are again safe investments. The loans can come from any direction. Inhabitants privately, other projects, external individuals. The interest is already maximised to a low level and anyone can decide to refrain from interest or to be paid back at all. In the end for the foreseeable future the majority of the funding comes from banks. The German ethical bank GLS is paving the way, and we are actively trying to convince the Dutch banks to get interested in financing such projects. So far results are slow and small. Another part of funding is coming from subsidies relating to the function of the building or aspects of sustainability. A lot of tax questions come up as well, but the Dutch system is not the least complicated at that. This knowledge of course is really useful to starting projects and copying the wheel saves everyone a lot of time. This goes for fiscal questions, as well as legal, financial, technical and all kinds of regulations.

The Syndikat has been an example in many ways, but all this local knowledge is something a network has to build up in relation to its national context. Even the cultural differences between Germany and the Netherlands are easily prevalent. It has taken Vrijcoop and will take Vrijcoop in the future a lot of effort to reach the ease with which the Syndikat moves in a consensus-based decision making with up to 200 people present. What helps is meeting up, sharing stories, visiting each other. And formally the Syndikat is a member of Vrijcoop, as Vrijcoop is a member of the Syndikat. It is nice to see this non-hierarchical tradition spread across borders. Practically this means that in the past individuals from the Syndikat and Vrijcoop have visited each other’s meetings and there have been collective meetings for knowledge exchange. In the beginning more regularly than now. Still there is not really any need for work to be done by the Syndikat and Vrijcoop together.

Besides the MS do you have international/transnational partners – or an idea for collaborating with other housing or solidarity economy organizations, networks across the continent?

I am quite interested to see initiatives within different national contexts, how they are building their own version of the same kind of structures. If not formally, all these different networks are in some way linked to each other. I may personally know people in the English Radical Routes, the French le Clip, people in Catalan projects, and I don’t even travel that much, others know other people and other networks. This is already spread across the globe, we can make this into solid connections. So, brush up your languages and let’s get to work!